Nadia Palliser

“What is found at the historical beginning of things is not the inviolable identity of their origin; it is the dissension of things. It is disparity.”

Michel Foucault, “Nietzsche Genealogy, History” Language, Counter-memory, Practice, p 142

I have been increasingly lost in data. Scattered, splayed, drifting and dispersed, the data inhabit the mental dwelling space of my computer. They circle in the wireless air and resound through the hardware, pulling me into all kinds of images, details, sounds and stories. Though

I have often suffered the consequences, it has become a favourite pursuit. Accordingly, digital ‘bits and bobs’ mingle with the flow of email. The ongoing loquacity of online dialogue interjects all activated programs. As interesting images surface, the workflow is

synaesthetically supported by freshly downloaded music. And now streaming media play behind overlayed documents, as I move myself through text.

More than just a pursuit, I realize I am living in a space with the data - a virtual reality if ever there was one. Up in a hot-air balloon of information, I waver between what I’m looking for and what I find: cutting and pasting, ripping & scooping pockets of tasty data. As much

as my personal processing strategies still need fine-tuning, I thoroughly enjoy the permanent condition of incompleteness that this practice offers me. Shaking off the constraints of overload, metaphors of superfluity soon melt as mnemonic tools materialize. This has not

resulted in thinking about data as non-information as Richard Saul Wurman would have (1). Being lost in data, though unfamiliar and awkward, is a significant way of absorbing information. In all its fuzziness and google wise-guy pretensions, its potential as a practice

of networked semantics is still to be explored further. I am interested in how these scattered forms of absorption and exchange relate to a contemporary form of historiography.

Online archiving is tentatively probing new kinds of venues. With theuse of query tools and semantics and the addition of dialogue as a means to exchange data, documentation has interesting territories to explore. As I work to create an online archive for ISEA – The Intersociety for the Electronic Arts – I ask myself how and where to begin this exciting project. Spread out over various cities of the world, ISEA’s nomadic manifestations host a broad range of media art and theory. From the sober musical experiments of Michael McNabb to Stelarc’s technocratic performances, its formal set-up has enabled an accumulation of tentative digital art to materialize. ISEA has continued to foster interdisciplinary academic discourse and exchange among those working with art, science and emerging technologies in the last seventeen years. With the up-and-coming ISEA2006 in San Jose California, the symposium brings a wide array of contemporary media art, design and theory to the fore. As ISEA’s networked and active history unfolds, I realize there are many threads to pursue. Apart from chronology, themes and communities intertwine, albeit the linearity of passed events. My question here, as I become lost in data again, is how the design of specific histories might relate to its different users and adapt to the distracted navigation of online dwelling spaces?

Fig 1 Labyrinth of Chartres

The labyrinth of Chartres (fig 1) has been a long time favourite of mine as a (symbolic) map of online dwelling space. Not surprisingly, as a structure for ritual, the labyrinth offers spatial dimensions to those who feel lost; i.e. the devoted Christian or otherwise the muddled information seeker. Since the labyrinth’s centralized form leads to divine truth or similarly to the essence of things, it was obvious that this was not the path to follow. As tempting as its symbolism might be, it had no actual bearing on digitally being lost in data. Besides, unified metaphysical knowledge is just too oldskool: as Venerable Jorge, the gatekeeper of an unknown book of Aristoteles bellows in the labyrinthine library of the film the Name of the Rose – ‘It is not the progress but the recapitulation, not the search for knowledge but the

preservation that is important”.

Since the happy digression of absolute knowledge, the search for information has thrived excessively. Supported by media that have become more and more mnemonic, there seems no need to recapitulate, at least not literally. We store, forget, and pick up later since there is not one truth to find but many. At the same time, though the generation of stored information might make recapitulation redundant, it also, ironically, triggers an aesthetics of memory. The faded nostalgia of analogue photography, for example, as described by Roland Barthes in Camera Lucida, appeals greatly to screen-based sensibilities. The transient uniqueness of that one-only silver-nitrate image is just like a scratch on a record. Bumps, blobs, and other mediated traces of use seem to materialize passed time. Sentimental perhaps or even melancholy these traces form a kind of visual or tactile historiography, something that digital preservation seems to lack in all its binary sobriety. A

good example of this is http://www.radicalsoftware.org: an online collection of the video art magazine Radical Software, published in the seventies. Users can access the archive in different ways, depending on what they are looking for. By maintaining the paper-based fragility of ink blotted letters and black-and-white photography in PDF format, the

history of the magazine upholds its activist atmosphere. In a way the graphic deterioration contributes to a tactile feel for the historical data.

Once a history becomes versatile, the emphasis on linear development softens and expands to other orientations. Megalomaniac overview moves to the background as ‘the singularity of events is recorded outside of any monotonous finality’. (p 139) The concept of genealogy as described by Michel Foucault in the essay ‘Nietzsche, Genealogy, History’ introduces a different way to deal with historical data. Genealogy, literally meaning ‘the successive generations of kin’, attempts to challenge the linear meta-structure that is projected on to history. Brainwashed by hundreds of slides as a ‘budding art historian’, I know I have been seduced by the nineteenth century format and its progressive timeline. As Foucault writes “We want historians to confirm our belief that the present rests upon profound intentions and immutable necessities”. Though nature might progress historically, there is nothing natural about history’s progression. According to Walter Benjamin: the nineteenth century conflation of nature and history is in fact a myth of social evolution, a construction of bourgeois enlightenment, manifest in the nineteenth century world exhibitions (Mythic History: fetish, p 80).

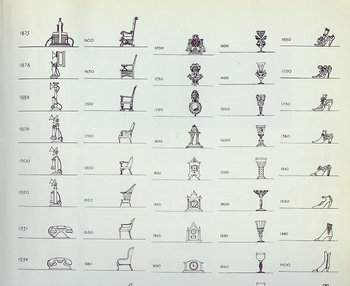

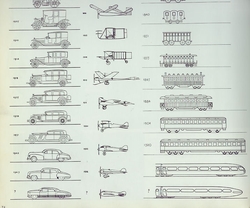

Fig 2 Raymond Loewy’s timeline

The timeline made by the designer Raymond Loewy for example (fig 2) illustrates the grand scheme of streamlined design (of which Loewy was a pioneer). As well as trains, planes and automobiles, you see a fashionable lady in dress and swimming gear at the end of the line. Not to my surprise, the feline female figure becomes slimmer and straighter as the years go by, ending in a question mark in the future, at the bottom of the page. Looking for a construction of history that looks backward rather than forward, Benjamin approached history as the destruction of material nature as it has actually taken place; a material history that provides dialectical contrast to the futurist myth of historical progress. Just as the spooky analogy of ‘The angel of history’ (2) (fig 3)

Fig 3 Angelus Novus Klee, 1910 (bought by Walter Benjamin in 1921)

“Genealogy must look for events in the most unpromising places, to what we tend to feel is without history – in sentiments, love, conscience, instincts; it must be sensitive to their

recurrence, not in order to trace the gradual curve of evolution, but to isolate the different scenes where they engaged in different roles”. In contrast to the fatalistic passing of

time and its inevitable moodiness (dramatizing the data), geneaology

is in the first instance gray, meticulous, and patiently documentary. Most importantly it defies the search for “origins”. (p 140)

According to Nietzsche in the “Genealogy of Morals” the search for origins is an attempt to capture the exact essence of things, their purest possibilities. (p 142, I haven’t actually read this book myself: after all, how far back does one go?) To search for origins, just as Venerable Jorge believed, implies a metaphysical, timeless secret that awaits those who seek “that which is already there”. To defy the search for origins however, cultivates the excavation of errors, details, (technical) failures and mistakes – the art of the accident perhaps. As

I begin to grasp the kind of material in the archive of ISEA, I realize that it is the physical presence of perishing documents which will make a practice in genealogy materialize. Playing chunky U-matic tapes of early computer graphic films, I need to soak up the quantity of source material by watching it closely; tracing sensually mediated ‘impurities’ as a scrupulous archivist. Only then can I begin to understand the materiality of what has endured the teeth of time.

The urge to make online data materialize in new and perhaps tactile ways loosens the emphasis on purely visual, digital information. At least to me, it offers new spaces of flow to think about information differently. Without sounding all too synaesthetic or utopian in a VR kind of way, as a backdrop for the further development of software tools in historiography, documentation can become so beautiful! Perhaps it might improve the otherwise so ‘hypermediated’ windows we still stare at or otherwise at least slow down the blind behaviour of information seeking. Things might emerge that are skimming under the surface, like a swarm of fireflies underneath instead of above the water. The contemporary pressure on documentation and digital preservation is perhaps justified in so far as the unescapable deterioration of analogue carriers creates some urgency. At the same time, online archiving as genealogy needs careful consideration. Both the need to process physically as well as the scattered semantics of being online should be taken into account. Materially processing data online might mean delving into different forms of tactile remediation but it may also manifest

itself in virtual conversation as a genuine means to find out more from personal contact. Different threads are possible as online archiving explores the permanent condition of incompleteness - to become knowledgeable while being lost.

(1) ‘Every one spoke of an information overload, but what there was in fact was a non-information overload’ – Richard Saul Wurman, What-If, Could-Be, Philadelphia, 1976

(2) As in the painting by Klee “Angelus Novus” - “His eyes wide open, mouth agape, wings spread. His face is turned to the past. Where a chain of events appears to us, he sees one single catastrophe that relentlessly piles wreckage upon wreckage, and hurls them before his

feet. [ …] The Storm [from Paradise] drives him irresistibly into the future to which is back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows toward the sky. That which we call progress is this storm. (p 95) Dialectics of Seeing, MIT Press, 1991

BOOKS

Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida, 1980

Umberto Eco, The Name of the Rose, 1983

Walter Benjamin, Susan Buck-Morss, The Dialectics of Seeing, MIT Press, 1991

Michel Foucault, ‘Nietzsche, Genealogy, History’ from Language, Counter-memory, Practice, Selected Essays and Interviews by Michel Foucault, trans. Donald F. Bouchard and Sherry Simon, ed. Donald F. Bouchard. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1977

Nadia Palliser

is freelance writer and currently works as

theory tutor at the Design Academy Eindhoven. She is also project

manager for ISEA - Intersociety for the Electronic Arts where she is

responsible for making their archive accessible to the public. Nadia

worked for V2, Rotterdam as webeditor and taught New Media theory at

the Willem de Kooning Academy in Rotterdam.

Comments